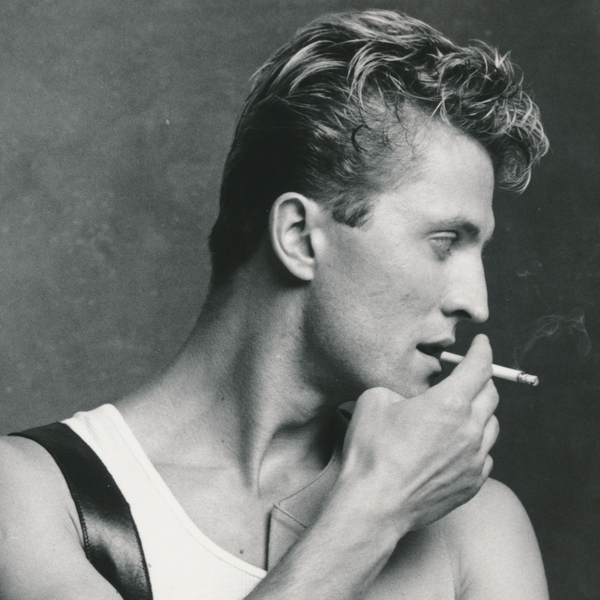

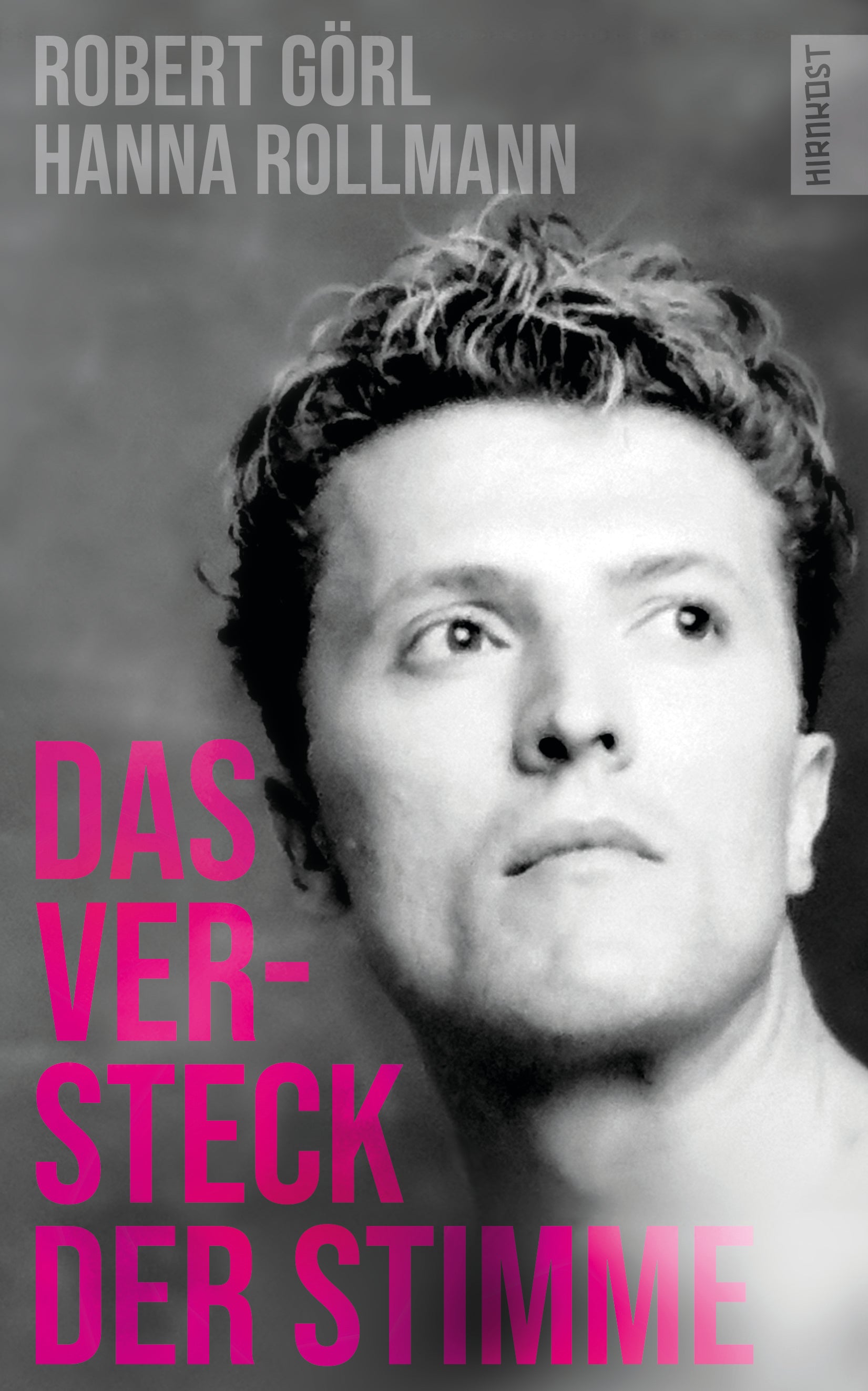

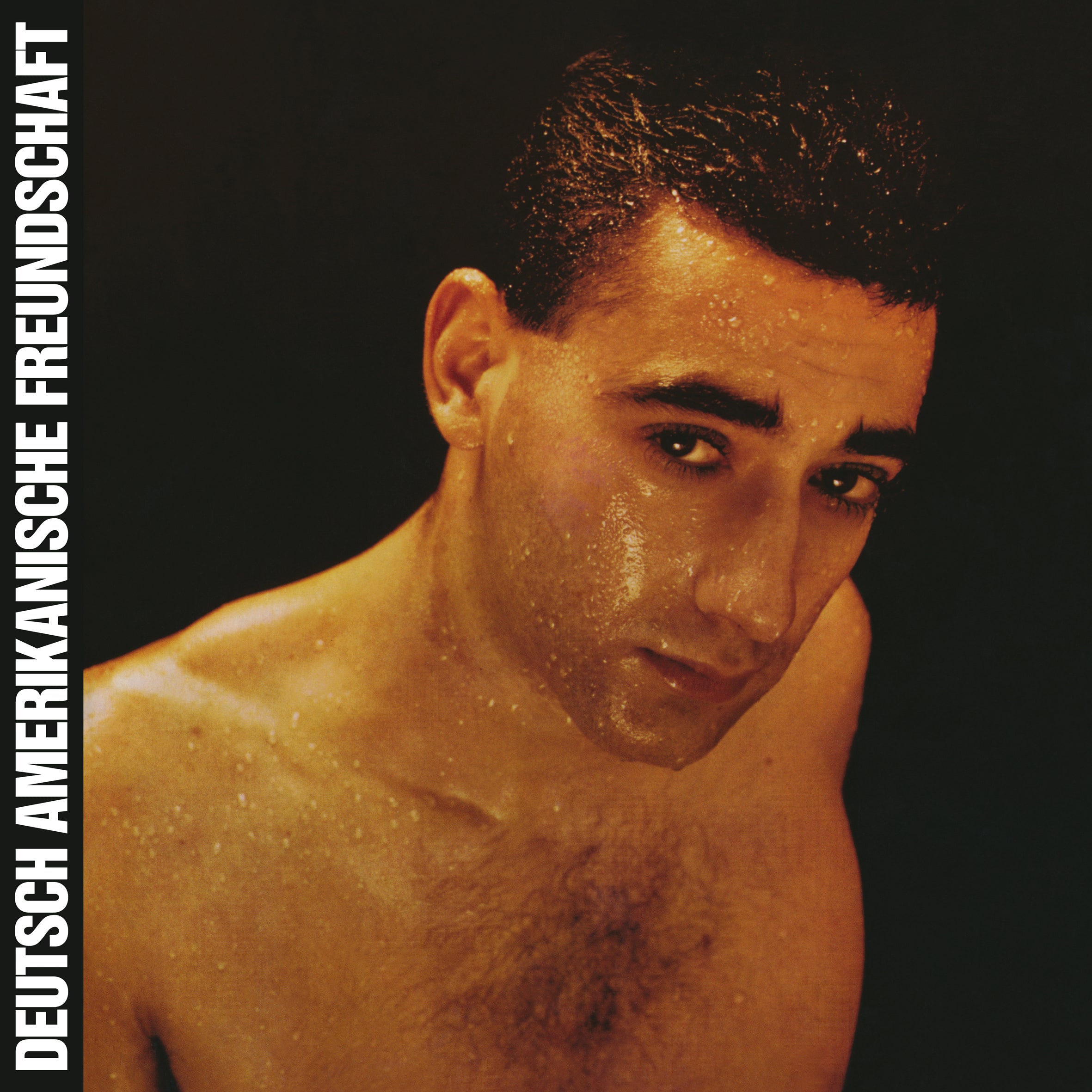

Robert Goerl

Robert Görl, of the legendary DAF, created poignant electronic sketches during a personal crisis in Paris. Using only an Ensoniq ESQ-1, he created emotional sounds that foreshadowed the future of electronic music. Born out of desperation, these sketches illuminate a creative resurgence amidst the depths of life.

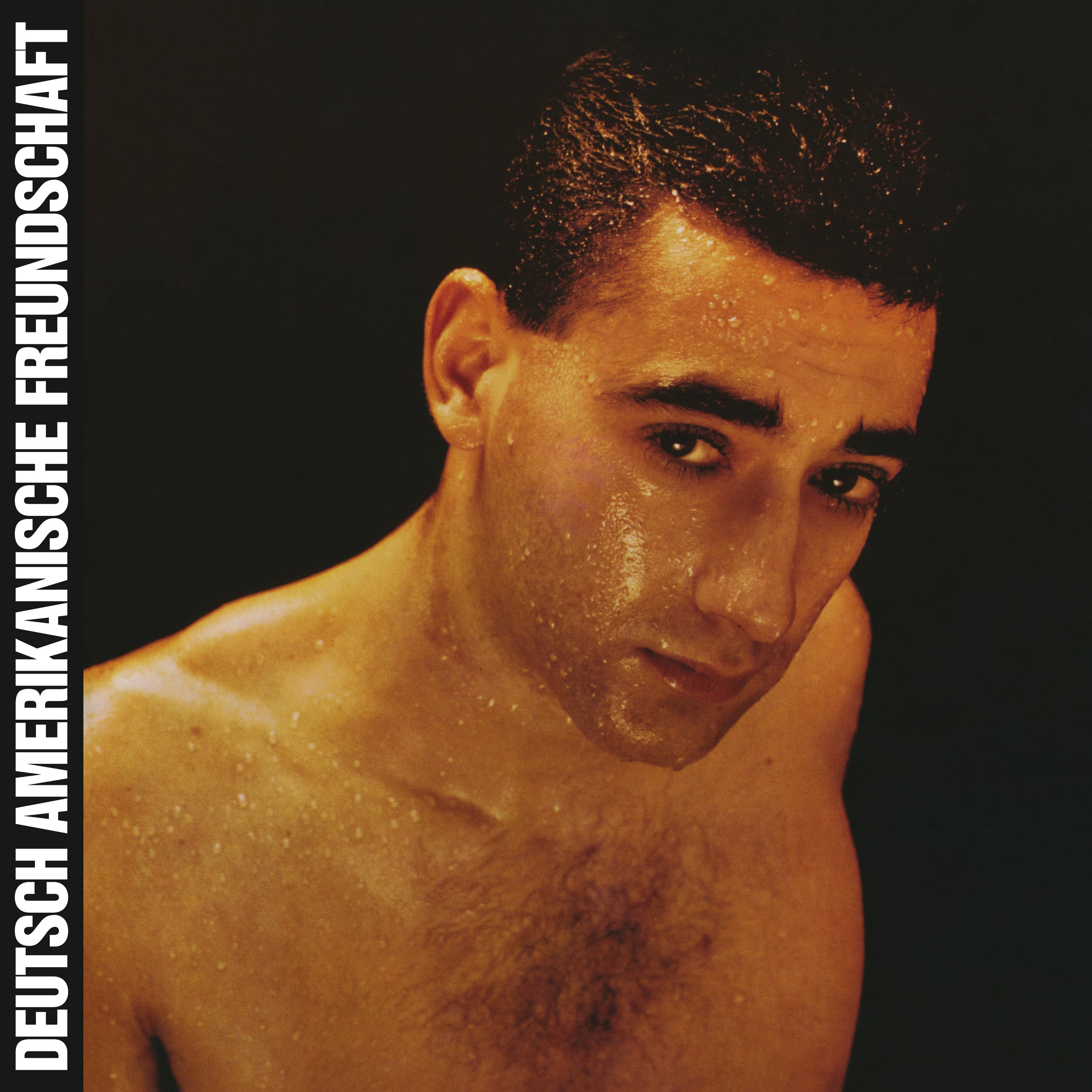

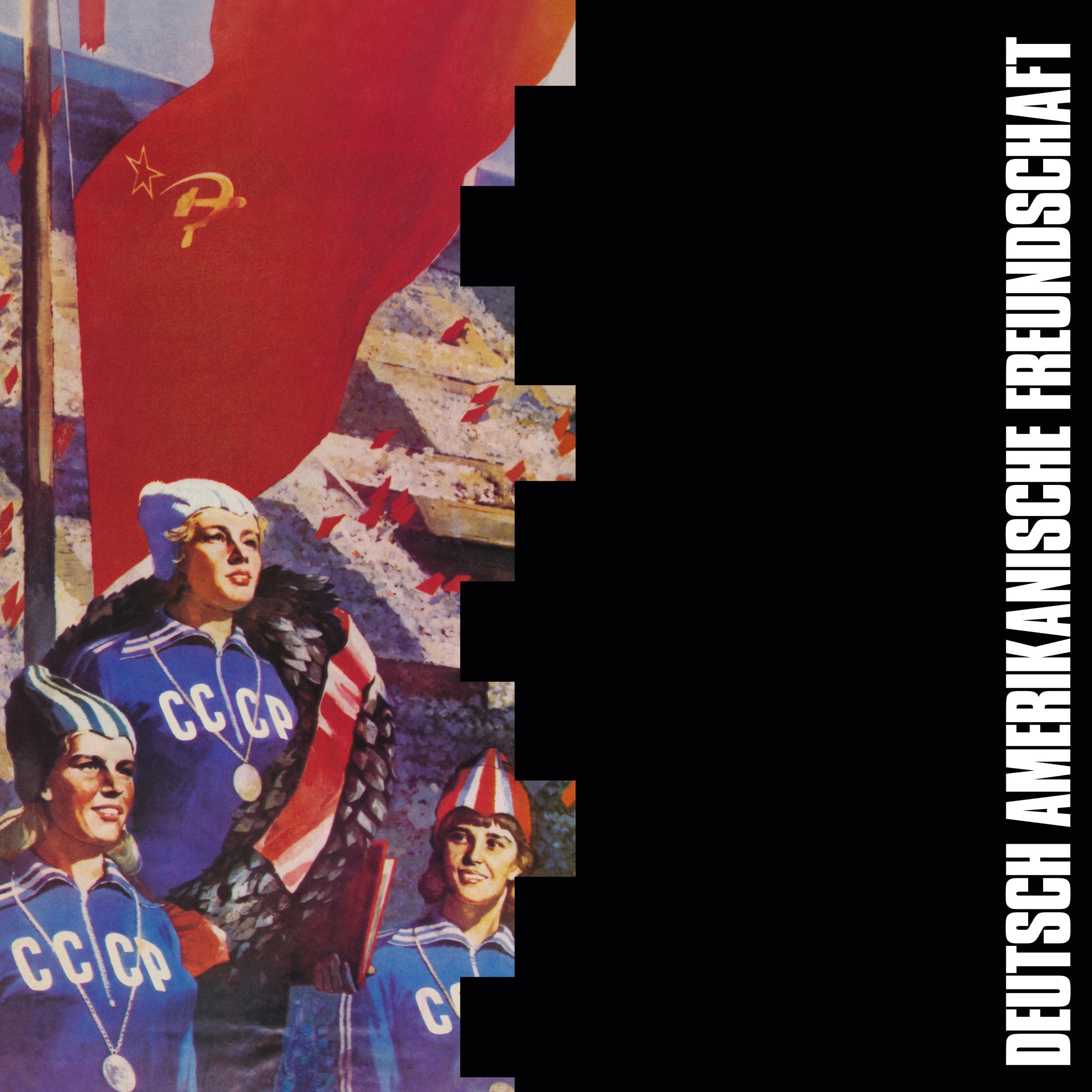

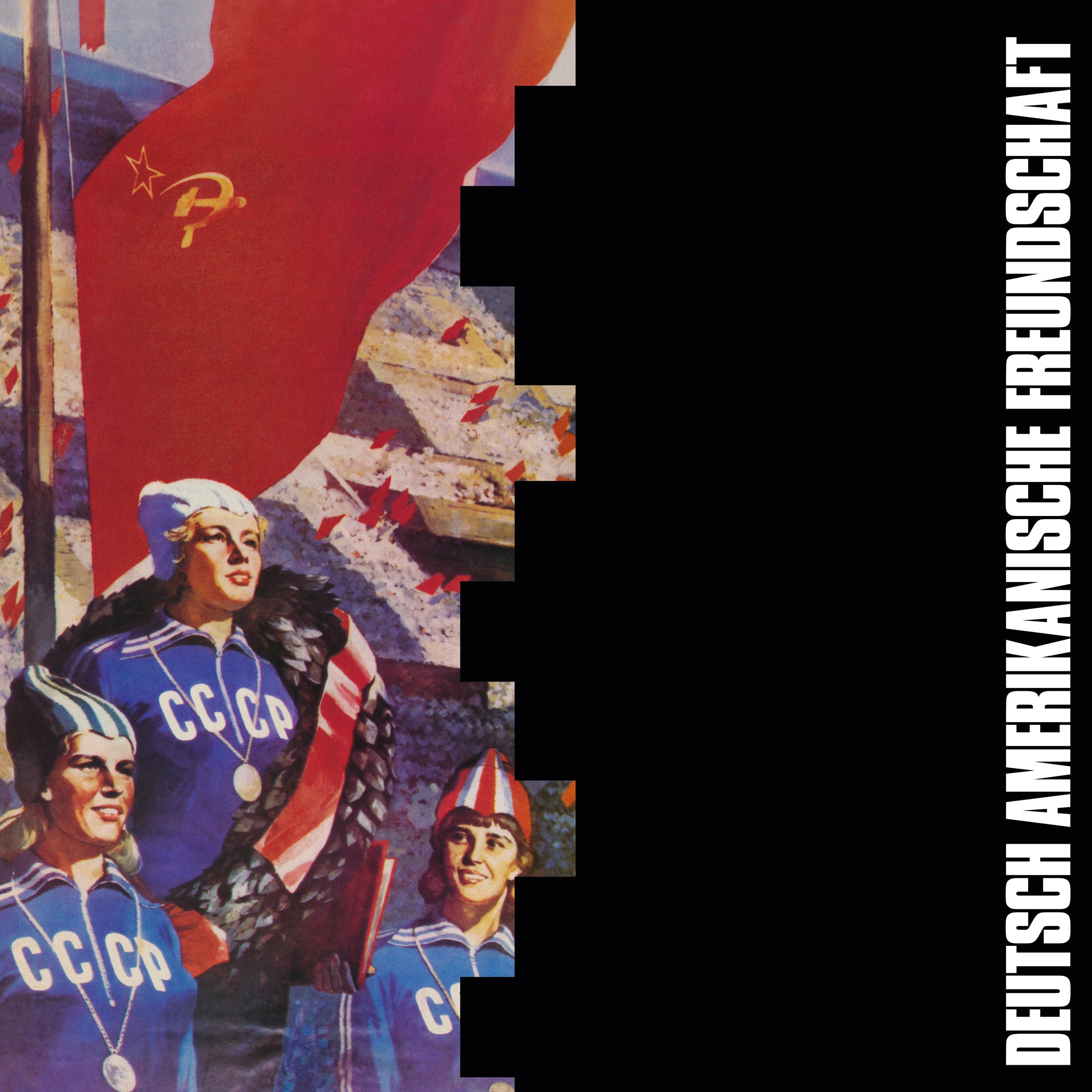

Everything begins with an end, but it doesn't end forever. In the early 1980s, Robert Görl and Gabi Delgado enjoyed great success as the duo Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft, until they split up in 1982 after a dispute. In 1986, after a short-lived attempt at a reunion, they split up again, this time for a much longer period. Robert Görl says that this time was very difficult for him and that he was deeply disappointed in his musical partner and friend; while working on the LP 1st Step to Heaven, they got in each other's way so much that he lost all interest in making music.

So he decided to try something new and went to New York to study acting at the prestigious Stella Adler Studio of Acting. He spent a semester rehearsing Shakespeare and other classics and might have had a career in the stage; but after returning from a short trip home, he was arrested and interrogated upon arrival in New York. The immigration officer asked him what he was doing in the city, he replied that he was studying acting - "That's interesting," said the officer. Four days later, Görl received a notice in the mail that he had violated immigration laws because he was only studying in the USA on a tourist visa; he must therefore leave the country immediately and is not allowed to enter the United States for the next ten years.

Not only did he no longer have a band, he could no longer study and could no longer stay in the city he had just learned to love. But that was only the beginning of his problems. When he flew back to Germany, he was detained at the airport. He was told that the German army had been looking for him for some time because he had evaded his military service; he was not allowed to leave the country and had to report to the army within a few days, otherwise the military police would arrest him. Görl thought about it for a few days, packed his few belongings in a suitcase, tucked his newly purchased synthesizer under his arm and got on a night train from Munich to Paris; sleepless and with a racing heart, he waited for the border control, which did not even open the compartment door for him. The next morning he stood at the Gare de l'Est and started looking for cheap accommodation. He was finally found in Levallois-Perret, a suburb in the northwest of Paris. His plan was to stay there for about a year, until he reached the age where he could no longer be drafted. He had a small room with a kitchenette and a sink. He knew no one in the city and did not want to meet anyone; even if he had wanted to, it would have been difficult since he did not speak French.

Now stuck alone in a boarding house in a Paris suburb, Robert Görl spent his days - and especially his nights - making music. He used his new, freshly released synthesizer - an ESQ-1 made by Ensoniq - it had eight voices, a built-in sequencer and thousands of pre-programmed sounds. It was a machine that could be used almost like the workstations that would simplify and dramatically change the production of electronic music in the late 1980s. In the solitude of his hermetic existence, Robert Görl managed to penetrate the future of music: night after night, he delved deeper and deeper into the possibilities offered by the synthesizer; he composed and layered music on top of each other; he shaped sounds, reworked them and sometimes deleted them again; he arranged rhythms and basses and modulated the music - especially the low notes - so much that they sounded more hissing and "dirty". As a result, the songs became more and more dramatic and personal. They reflected the life crisis that Görl was going through, but at the same time they were a timely remedy to free him from the feeling of being trapped in a failed existence.

He stayed in the boarding house in Levallois-Perret for six months before staying with two of his sister's friends. But after nine months in Paris, he felt he urgently needed to return home. And he was lucky: when he returned to Munich, the German army left him alone. Things started to look up. The time in Paris had given him new optimism and rekindled his passion for making music; he decided to make a pop album out of the songs he had composed on his ESQ-1 and recorded on commercially available cassettes. He flew to London to meet Daniel Miller, who had released DAF's first albums on his Mute Records label. Miller put him in touch with Dee Long, a progressive rock musician who was playing in a new wave band at the time. In Long's studio in southern England, Görl and Long made new arrangements of Görl's Paris pieces. Afterwards they wanted to rehearse and record the music in Beatles producer George Martin's Air Studios. Before that, Görl visited Munich one last time to visit his brother outside the city gates. On the way home he crashed into a tree at high speed after losing control of his car on an icy road.

Görl spent half a year in hospital and in a rehabilitation clinic. The doctors tried with all their might to save his life. His right arm was shattered and had to be reconstructed with steel implants; he could not move his legs for several weeks and had to learn to walk again. Robert Görl was only able to escape the crisis for a short time before he plunged back into nothingness; this time, however, nothingness immediately opened up new possibilities for him. When he was released from the hospital, he returned to his apartment, which was empty. His friends in Munich had not expected him to survive and had divided his belongings among themselves; years later, one woman proudly told him that she had slept under his old duvet. But he didn't miss any of it, neither the duvet nor his other possessions; he also had no desire to make music. During this time, he never once thought about the album he had been working on before the accident. Instead, he went to Thailand to become a monk in a Buddhist monastery. He spent three years there until he realized that he couldn't find what he was looking for in a monastery, but only within himself. So he returned to Germany in the summer of 1992 and danced at the Love Parade in Berlin to music that sounded like it came straight from DAF. He spent the next few years as a techno DJ, but that's a whole other story.

A cassette with the unfinished songs from Paris, the dramatic, haunting, sometimes foul-sizzling but always delicately crafted pieces that Robert Görl had recorded during the deepest crisis of his life, turned up years later in a suitcase that he had deposited in his brother's barn. They are musical sketches; Görl says he never felt the desire to make a proper album out of them. They are sketches, but in them a whole time speaks to us, a life at a turning point, and the light that shimmers over the dark underbelly of the foul-smelling beats points us to the future: everything ends where something begins.